The bizarre link between rising sea levels and complications in pregnancy

Exposure to salty water can rob women of their reproductive organs and pregnancies.

The creep of seawater inland

While global salinity monitoring is spotty, evidence of saltwater intrusion continues to grow.

Electrical conductivity value (µS/cm)

10K–100K

100K–1M

1M–10M

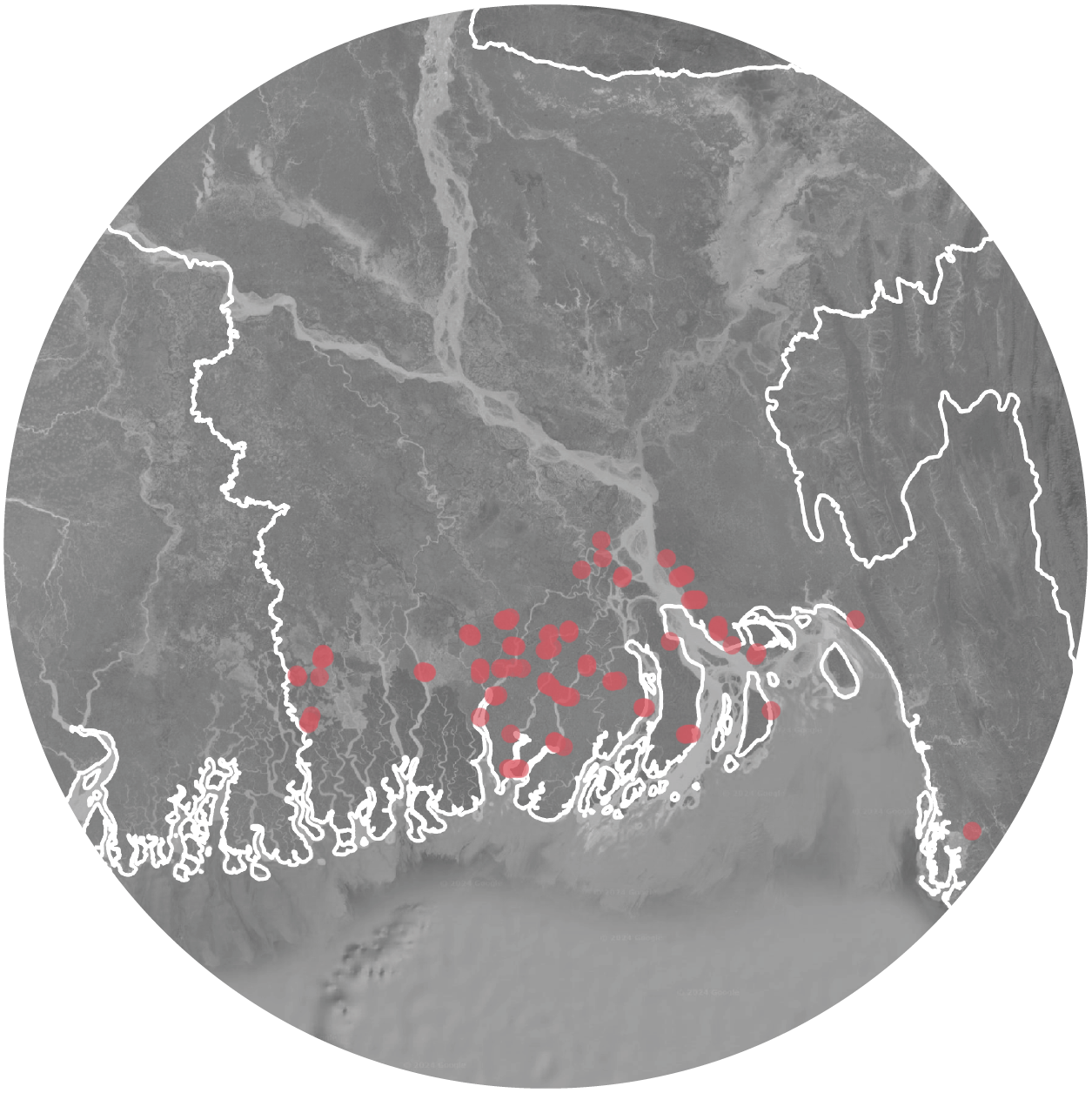

Bangladesh

Bangladesh

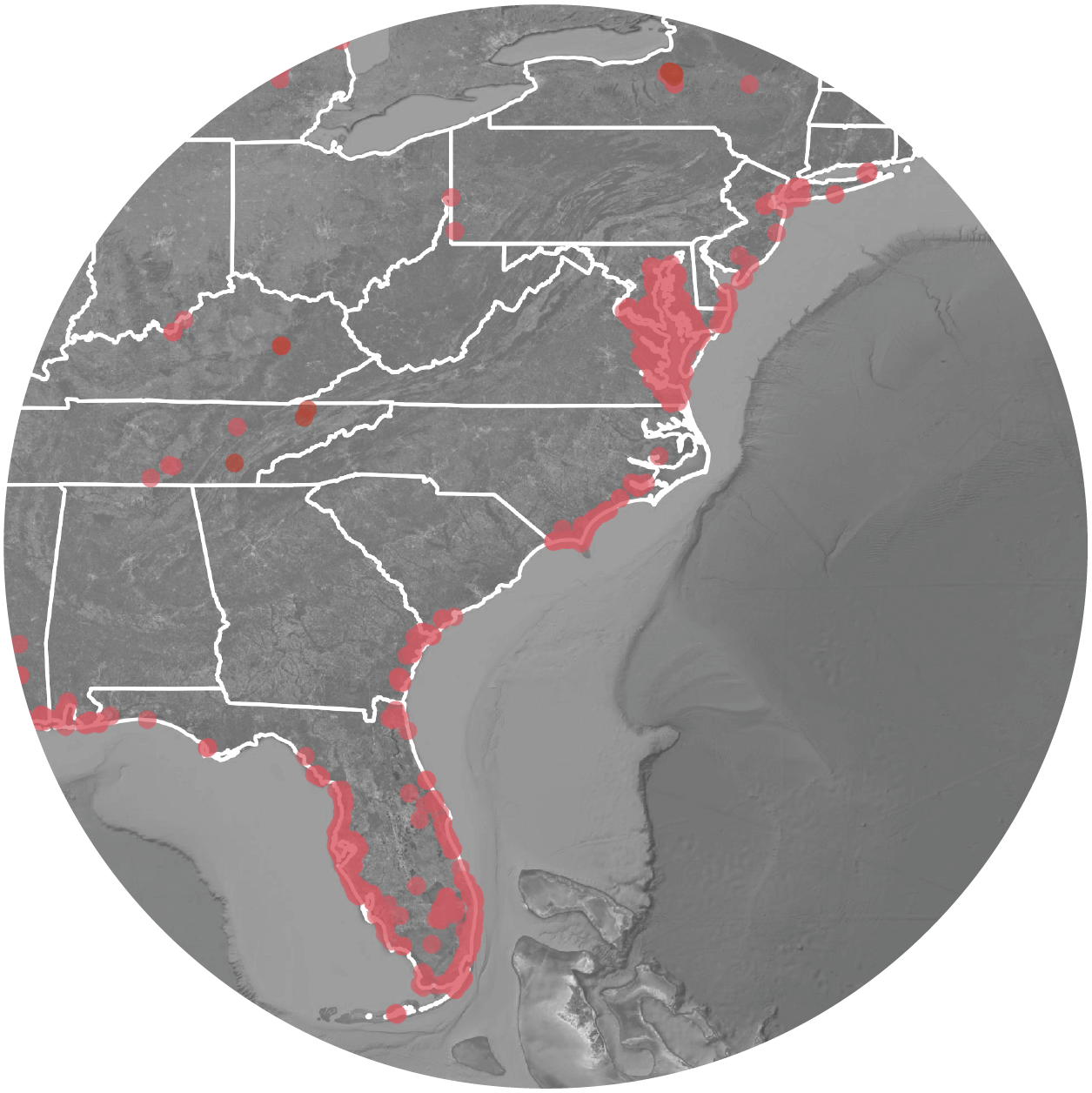

U.S. Atlantic Coast

U.S. Atlantic Coast

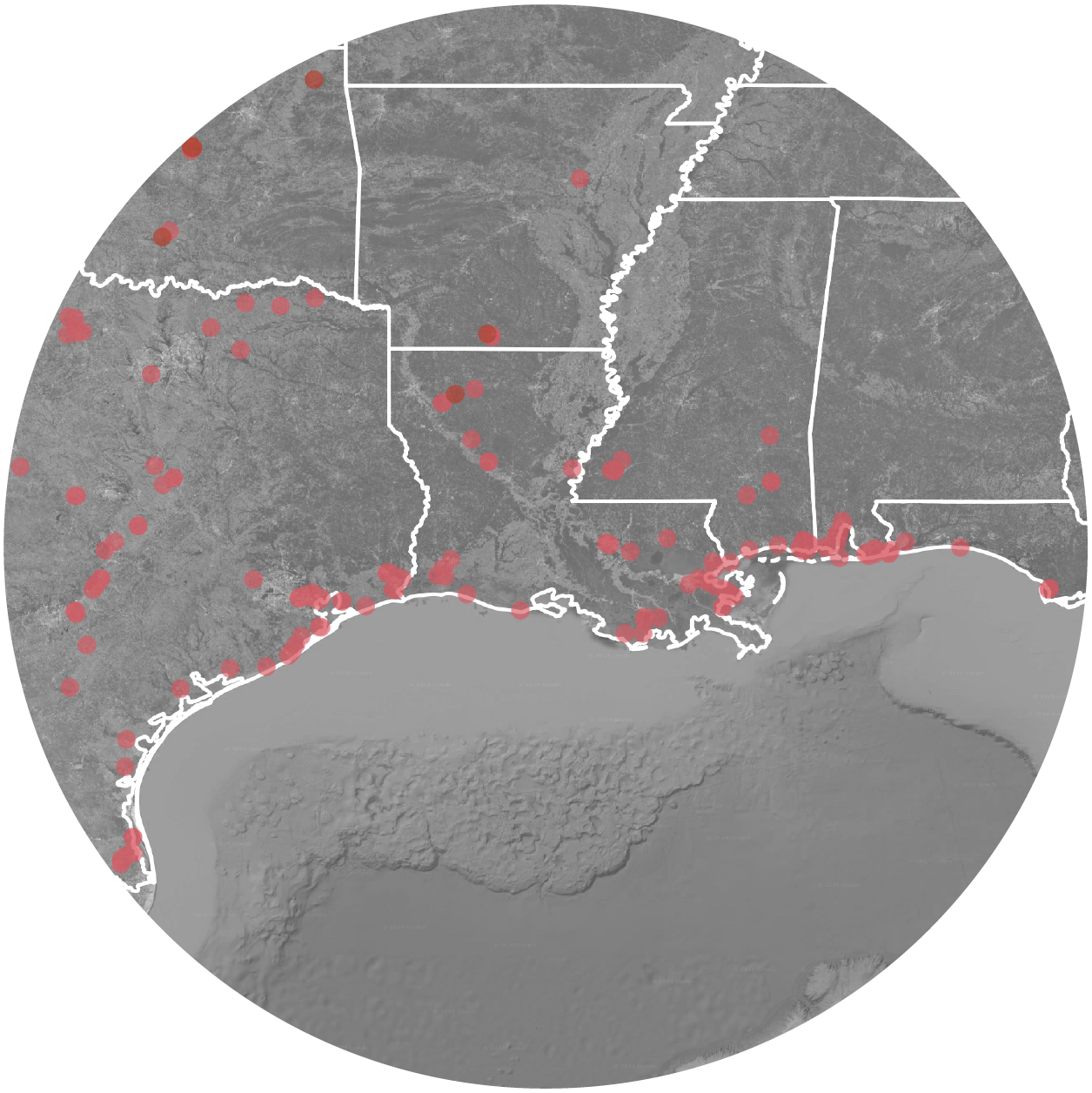

U.S. Gulf Coast

U.S. Gulf Coast

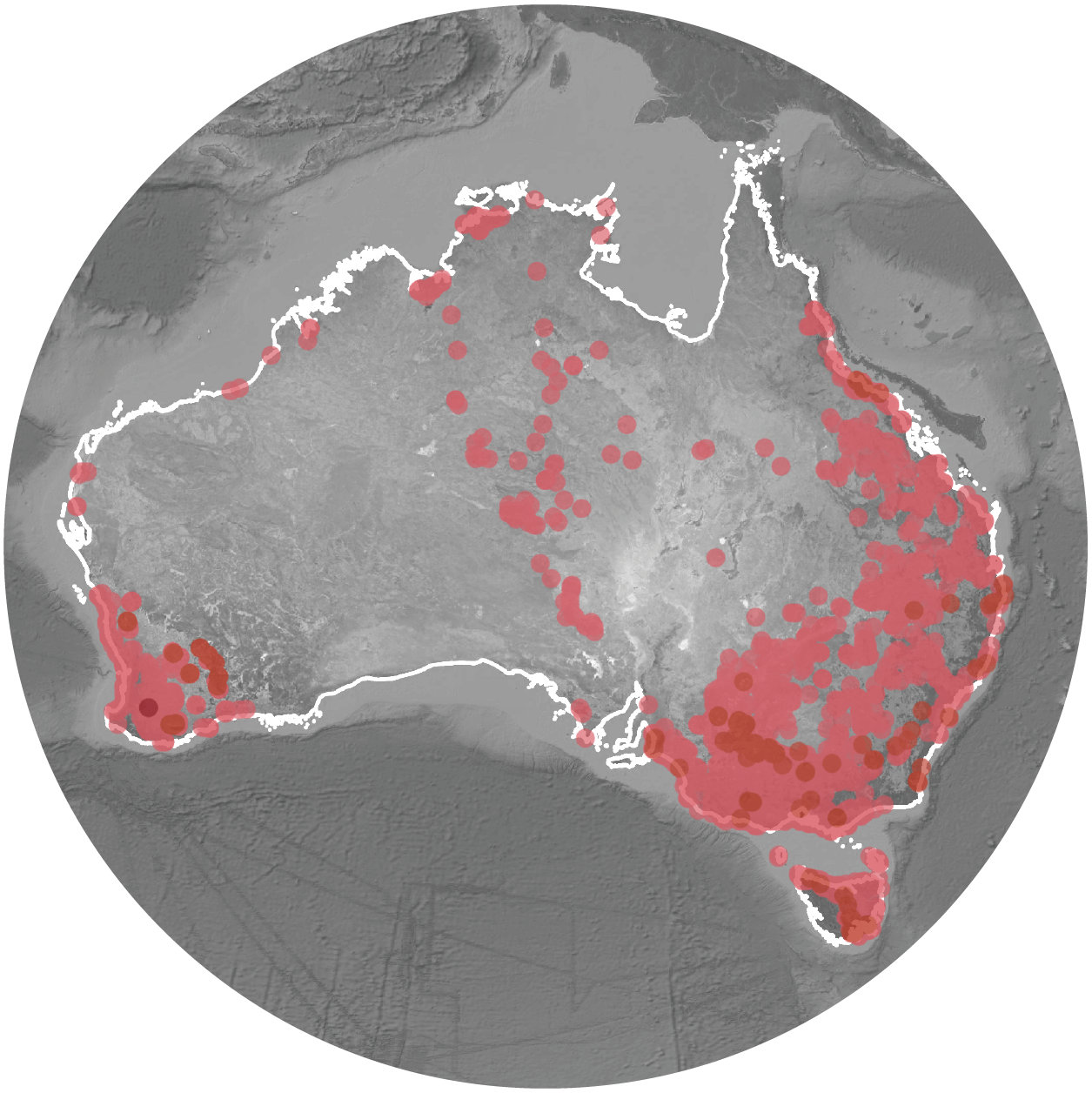

Australia

Australia

Source: Thorslund & van Vliet 2020 | Clayton Aldern / Grist